Word Count: 2700 | Reading Time: 9 min

When I was in class five, I borrowed an unassuming looking book from the school library. It was titled The Dark is Rising and it was by a British author named Susan Cooper. The book promised a tale based on Arthurian legend, which I was vaguely familiar with at the time, as well as ideas found commonly in fantasy books, namely that of the age-old battle between good and evil.

My journey with Susan Cooper was an individual one. The school library was where I discovered the strangest assortment of books, all equally available to us, no matter our age. This was all thanks to an elderly librarian who would shush us at the slightest provocation but who could never be bothered to check the age appropriateness of the books I brought to her to be stamped. That is not to say that The Dark is Rising was something that a ten year old shouldn’t read. On the contrary, I would say that I discovered it at the perfect time. The book was dark (though I mean no pun on the title here), the action taking place in the dead stillness of winter, the cold and dread of the Dark creeping over the protagonists lives, and dfc the reading habits of one little girl in Lahore deeply.

Much like what we expect from most fantasy books, The Dark is Rising started with a poem, one that I am proud to say I committed to memory and could probably still recite if you asked me to today. It also had an enduring symbol attached to it: a set of six circles, quartered by crosses. I wrote out the poem in notebooks and on plain pieces of paper whenever I could. On all the pieces of paper I decorated with that poem, the quartered circles accompanied it, the scattered pages marking out my lonely cult of one with regards to the series.

***

While The Dark is Rising inspired me to create visuals on my own, I consumed many other books that came fully illustrated and added to the magic of the stories I read. The Treasury volumes of folk tales, available only at the Ferozesons book fair that would visit my school every now and then, came in a box of a colour corresponding to the cover and were tied shut with a silk ribbon, the epitome of luxurious storytelling. Notably, I and a close friend I consulted in order to track down the names of these collections, both have ours still in our respective childhood bookshelves in Lahore.

published by Marshall Direct Learning

Humans are visual learners, anything that has an illustration added to it becomes easier to grasp and enjoy, no matter what age we are when we interact with an illustrated work. The Treasury folktale collections in particular, fascinated us as each story was fully illustrated, with the characters representing the relevant cultures the stories came from. This exposed us to different visuals from the world over. Such was the power of those illustrations that my friend and I still remembered the illustrations more than the actual stories.

Despite my long standing fascination with illustrated tales, one might realise that the narratives and stories I’ve highlighted here are distinctly lacking in one aspect despite their seemingly global scope. None of the books I read that fell into the speculative fiction genre were based in Pakistan.

I was largely a reader in English, and hadn’t even been exposed to the Umro Ayyar digests that most people have when growing up. My only connection to Urdu books outside of the school syllabus was the Inspector Jamshed series, one I read happily with my mother, a long standing fan of mysteries though she has shifted to televised versions exclusively over the years.

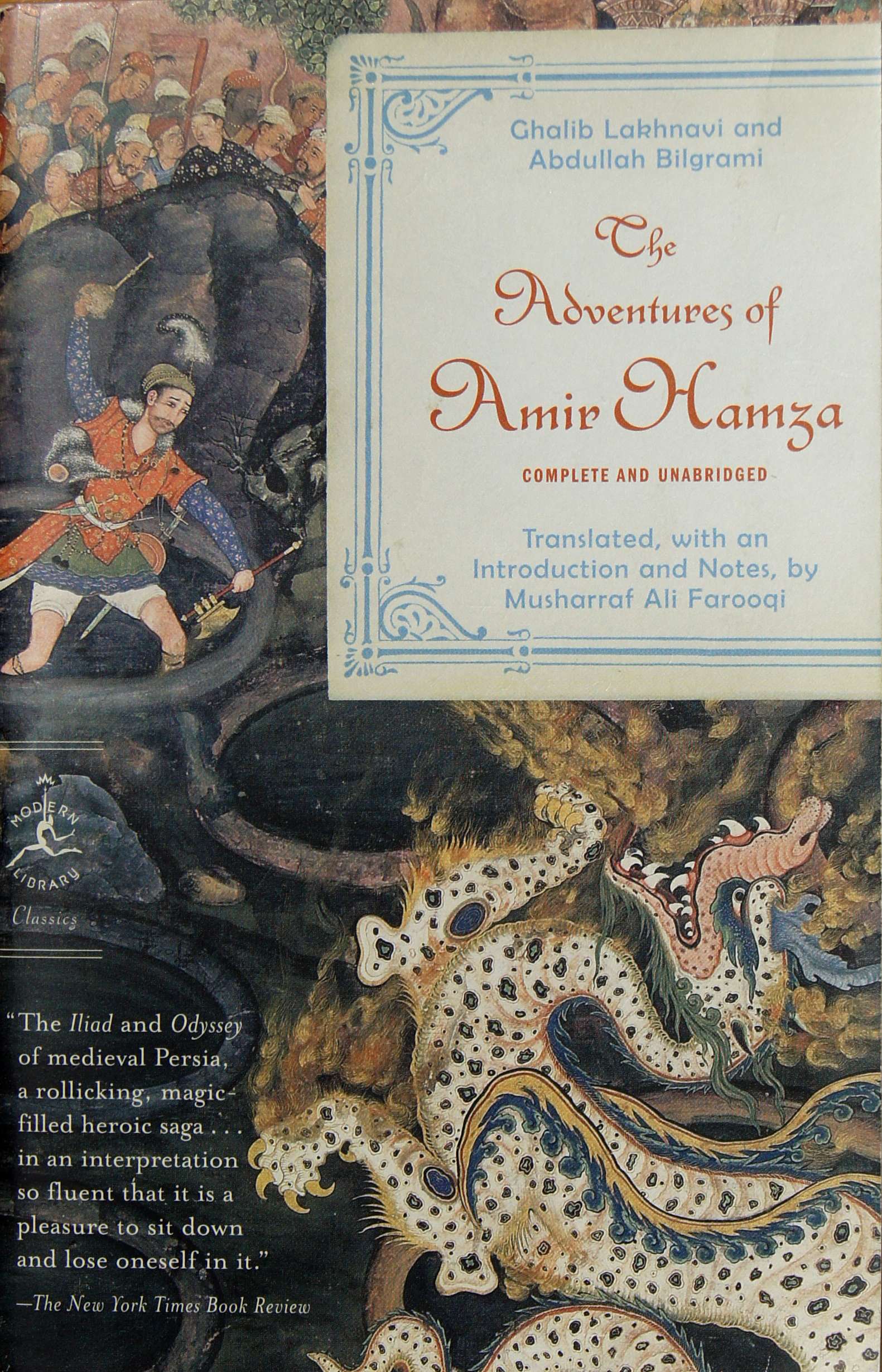

Cover for Dastan-e-Amir Hamza, translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi

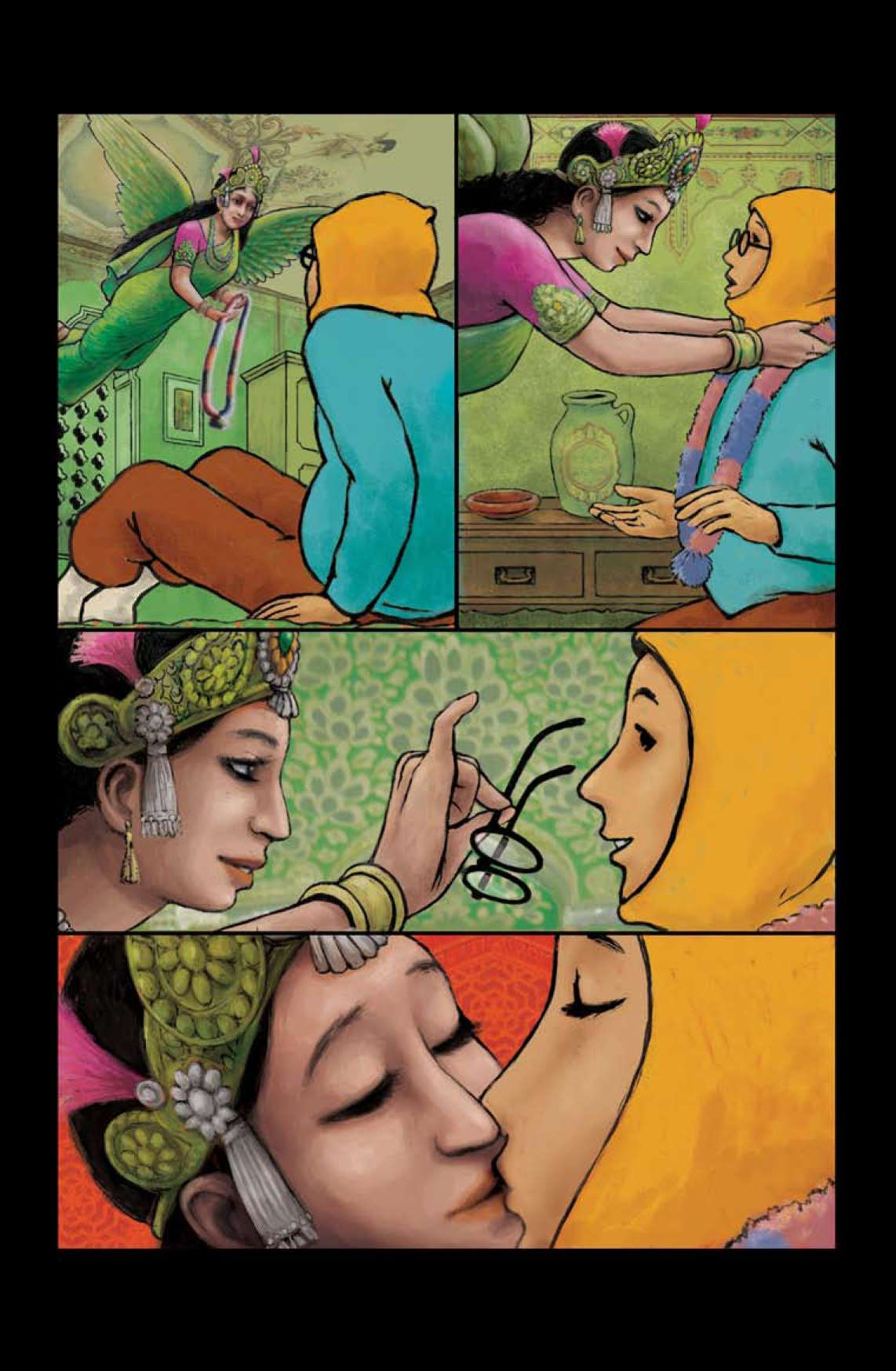

My first proper exposure to Dastan-e-Amir Hamza came with my eldest sister’s purchase of the nine hundred and so page translation by Musharraf Ali Farooqi. Reading it in the summer vacation before starting the final year of my undergraduate degree was eye-opening to say the least. Such an intensely wild and weird tale, full of romance, battles, and more violating acts than I knew how to react to, meant that I was hooked. I proposed turning one of its chapters into a comic book as my senior thesis, taking cues from the lovely and detailed folios that were constructed in Emperor Akbar’s time. An intriguing example of illustrated storytelling, the folios resulted in the development of a style of Mughal miniature that combined Persian and Indian approaches to painting. Given my childhood inhalation of American comics I fashioned my version of Amir Hamza and Aasman Peri after superhero visual tropes, muscular men and skinny lithe women in South Asian and Persian attire and weaponry. When researching visual references for the work I looked at Buddhist art as well as illustrated versions of the Ramayana to try and match the immense breadth of the stories contained within that volume.

Dastan-e-Amir Hamza and its illustrated folios have stayed with me for roughly eight years now, even as I develop illustration courses that can be taught to undergraduate students. It’s a narrative I highlight every time I talk about Orientalism and its visual depictions as well as the importance of telling one’s own stories. It’s the story I go back to time and again when I want to expose my students to the possibilities of illustrated storytelling that straddles performance as well, the courtiers in Akbar’s time holding up the relevant folio that illustrated what the dastan-go was reciting at that moment. My students have sometimes heard of Amar Ayyar (though they recognize him more easily when I call him ‘Umroo’) but often have no idea who Amir Hamza is. This fantastical story, so tied to the subcontinent and its mishmash of Islamic mythology and more cultural creatures – where the King of Ceylon and a simurgh and dragons exist simultaneously, where the lead character is married to the princess of the peris and feels obliged to return to his earthly love – is rife with rich visuals that should be adapted on a larger scale to expose young Pakistanis today to this tale. Attempts have been made, I myself own a comic book version of ‘Umru Ayar’ where the sheer beefiness of the character makes him more a He-Man-esque figure, and less like the less physically imposing trickster we perhaps might remember him as.

Having shifted into the realm of teaching, I have been struck by the stereotypes and tropes my students are sometimes unconsciously reproducing. Once an in-class exercise asked them to make a zine based on their favourite season. Almost everyone who picked ‘winter’ as their choice drew snowmen, one student drew a hunting lodge – complete with a buffalo head decorating the wall – while another drew skis and puffer jackets. All my students were from Lahore. It was interesting to note how our minds have been conditioned to see these images as soon as we hear the word ‘winter’, how perhaps these students didn’t even think to interrogate for even a second why these were the images that came to them.

I have also been in touch with American art students, presenting my work on Orientalism and world building to them. The concerns they raised were interesting, and indicative of the more culturally diverse exposure they had. Their main issue (especially for the white students) was how to borrow or be inspired from other cultures without stealing or appropriating. I gave them the examples of Avatar: The Last Airbender and Samurai Jack, two animated shows where the influence was felt in every frame, but then, so was the admiration and research into the cultures that inspired them. On the flip side, one of my Pakistani students asked how to create unique illustrated narratives when ‘most of the stories had already been told’ (I’m paraphrasing their more nuanced question). This issue was raised in the class where I teach comics, an artform I love with every fibre of my being for its potential to showcase narrative storytelling in some of the most unique and exciting ways. To that student I pointed out that while many stories, especially those of the fantastical had perhaps been told in some way or the other, they had yet to be told in a Pakistani context at the scale with which we perhaps think of them in an American one.

What does a zombie invasion look like in Lahore? What would Colombo look like underwater in a post-anthropocene era? What about a glance into the djinn film industry in Mumbai? In a similar vein, a Pakistani vampire story would look completely opposite to one set in eastern Europe. Just the switch of location would change the entire basis of the story. Does Dracula lurk in a fancy mansion in the city’s exclusive residential area? Would he eschew a cape in favour of a Pashmina shawl that he could throw around his shoulders dramatically? What happens when these stories become illustrated? What are the idiosyncrasies present in a Pakistani city that an illustration would help bring to the forefront, and why hasn’t it been done to the level of existing beyond these rhetorical questions yet?

Questions like these fill me with so much glee because there are so many stories that have yet to be told in a Pakistani context. Being able to work firsthand with the young people who will (if I can inspire them enough) create illustrated speculative imagery and stories is as frightening and exciting as one can imagine. Showing them the work that already exists in South Asia, visuals that utilise our tropes and motifs and patterns in wholly unique ways is my favourite part of teaching courses like these. Thankfully there are so many examples to put forward.

***

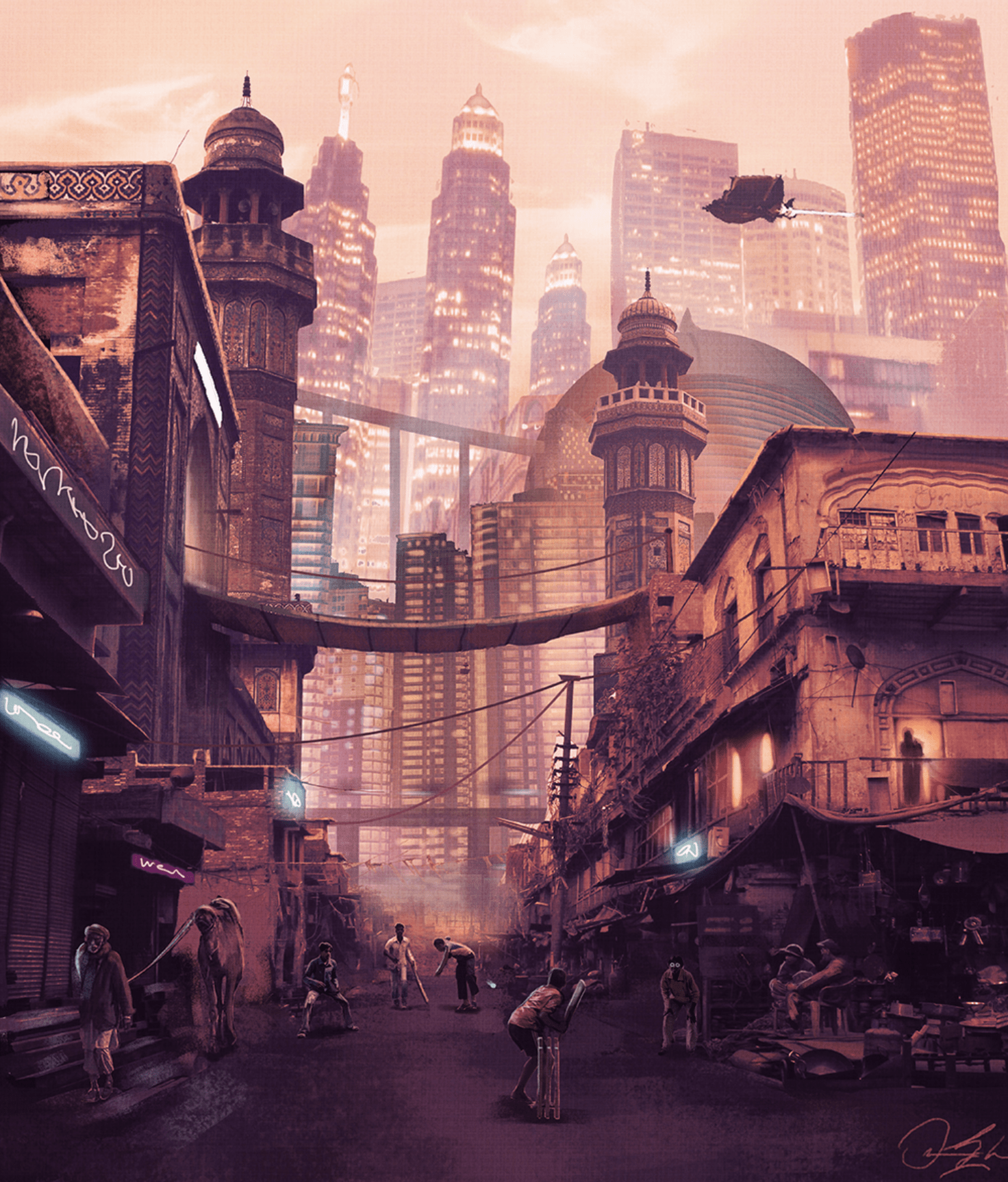

An illustrator like Omar Gilani shows that children don’t have to go through the trouble of dismantling their game of street cricket if one introduces flying cars. His futuristic cityscapes give one a new way of envisioning a Pakistani urbanity. The fact that most of his imagery acts on its own, with no textual narrative already attached to it, means that there are many rich stories that people can write based off of his images. The symbiotic relationship that text and image often share feeding into each other here where stories can sprout from visuals and take on lives of their own.

An illustration from the Pakistan + series

Across the border, the prolific graphic artist Orijit Sen’s surreal story Emerald Asapara shows the idea of love conquering all but using imagery much closer to home. Three wordless pages are enough to create deft narrative and the characters expressions and body language have you rooting for them despite the silence brought about by the lack of words. On the flip side, Komal Ashfaq uses text and different fonts to differentiate her characters in her popular webcomic Karachi but Haunted. A cast of fantastical creatures of both epic mythology and specific Pakistani urban legends inhabit the same geographic space of a comic panel, the Instagram friendly squares she employs moving the narrative forward in unique and humorous ways. A favourite panel of mine has a Buraq make her entrance by declaring that another character cannot be killed as he is a motivational speaker.

Page from Emerald Aspara

Panel from Karachi but Haunted

The Buraq as an entity often makes its way into the work of Sana Nasir as well. Nasir’s work is not only a visual delight but she often provides context for every element she includes in her illustrations. One only has to read a single caption from her Instagram to understand the richness she imbues her work with by the intensive research she does into the mythology of this region before rendering it in her sumptuous colour palettes. Her almost academic approach to image making makes the visual clues all the more rich and interesting to engage with. If you spot a creature or symbol you haven’t seen before, you can rest assured that it will have some greater significance in Islamic or Pakistani mythology.

Musafira

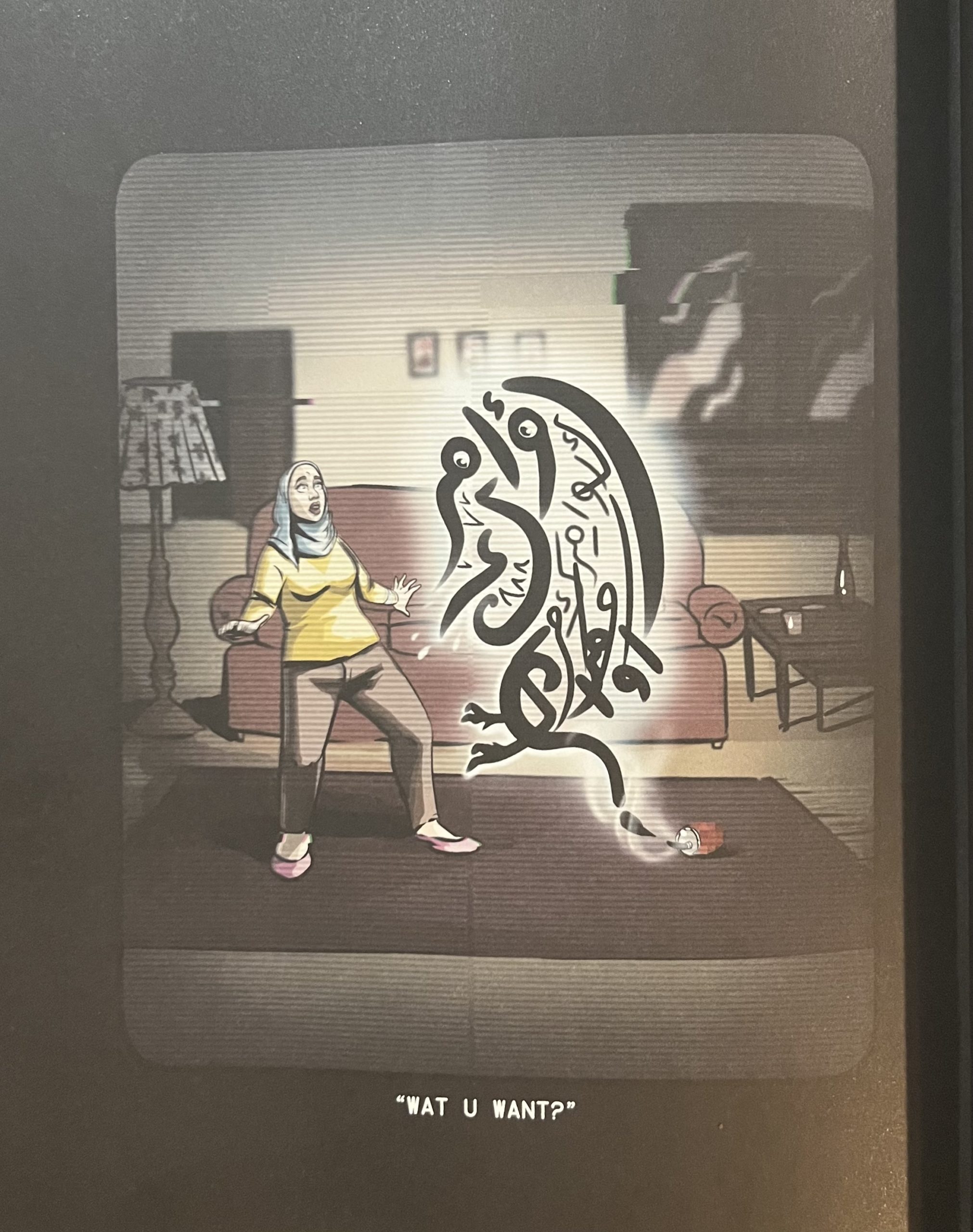

Most recently Deena Mohamaed’s graphic novel Shubeik Lubeik is creating buzz for its rendering of a Cairo where wishes come true. Mohamed’s unique page compositions and decision to render the wishes as living calligraphic beings lend the story immense charm and, as the writer Saladin Ahmed stated, reinforces “the uncanniness of djinn stories”.

Interior page from Shubeik Lubeik (Your Wish is My Command)

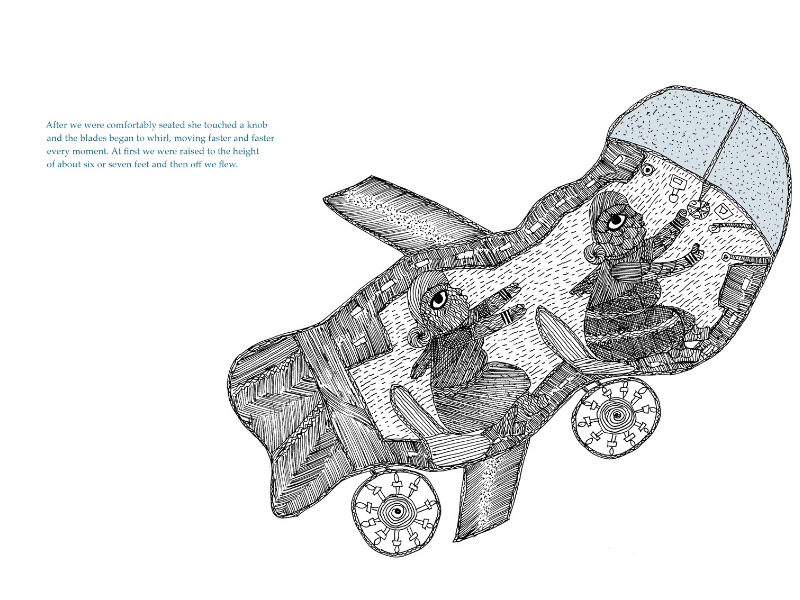

It is also fascinating when different artists take a stab at the same text. My favourite example to give is that of Sultana’s Dream by Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, which has been committed to illustration in delightfully varying ways. Durga Bai’s illustrated book takes cues from the art style of her tribe in the forests of India where one of the gods they worship is an artist and maker, and hence every act of illustration becomes a form of devotion. The textures and patterns she illustrates are directly inspired by the nature within which her tribe exists and make for a lovely set of almost tactile images. Shehzil Malik’s interpretation showcases most of the story sans text, a landscape meandering of Sister Sara and Sultana as they make their way across Ladyland. Drawn in a flat style that forces the viewer to consider each element in the illustration more carefully, the science-driven elements of Ladylad mimic the organic shapes of the vegetation Malik draws, making it difficult in some instances to separate the two. In contrast, Chitra Ganesh’s version looks like a science fiction pulp magazine, much like those that she takes inspiration from for her art practice. The scientific elements are on full display, with Ganesh adding her own embellishments like the floating head of a woman with a cog wheel under her neck driving her movement. I always enjoy highlighting the different ways this text in particular has been rendered by such artists, not only because the story remains refreshingly original but also to show how the artist’s context can change the images made in response to the same prompt. A simple and obvious statement to make, but one that I think holds importance given the South Asian background and wildly different approach of the three women I’ve highlighted here.

Interior page from Sultana’s Dream, published by Tara Books

I will continue to do my part, to show my students various artists they can take inspiration from – acknowledging that there are many missing from this collection of words I’ve put together, both historical and contemporary – while encouraging them to come up with their own fantastical versions of the world they live in. Speculative fiction as a genre is one of the most delightful ones to work in, inviting all to add their own versions of a future or a past they would like to see by allowing all types of stories to co-exist. The possibilities are endless, and while speculative fiction prose is taking off in Pakistan thanks to a new, emerging readership and initiatives like The Salam Award that directly foster such endeavours, I personally can’t wait to see more people adapt our stories and myths to the visual realm. Maybe one day another little girl will be copying out symbols from an illustrated book that opens her mind to not the legends of a country far away, but of one much closer to home so that she doesn’t have to wait until she is much older to start working on those visuals for herself.

Sultana’s Dream, digital illustration